Bear

Reviews

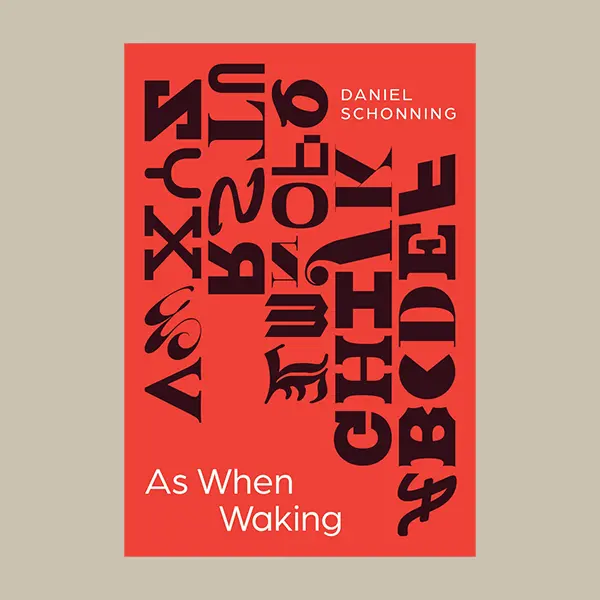

As When Waking

Daniel Schonning

—

A Reverential Encounter with Language

Daniel Schonning is the dear friend of a dear friend. I’d heard stories about him for close to a decade before the one time we ever actually met: at our shared friend’s wedding, for which Schonning served as the officiant. If you read As When Waking (The University of Chicago Press, October 2025)—and I very much hope you do—you will understand why Schonning was asked to perform a wedding ceremony. This book is reverential. Schonning’s poems are both steeped in tradition and utterly their own: a marriage between influence and innovation.

First and foremost, the book is devoted to the alphabet, to letters themselves. Of the book’s nearly 40 poems, 26 are abecedarians: they are written A-Z, then B-A, then C-B, and then finally Z-Y. According to the book’s description from the press: “This structure is tied to Jewish mystic texts such as the Sefer Yetzirah, which probes the relationship between the letters of the Hebrew alphabet and the world they inhabit.” But even if you are not someone intimately acquainted with the Jewish mystic texts, as I am not, right away you can sense a devotion to the divine from the all-encompassing voice of the book’s “Proem:”

And when the storm subsides, the catch basin

coos; the sky exhales; the dead rosebush withers;

the bright kingfisher paces in the sand.

And all night, the lemon tree remembers

sun. And the bathhouse cradles the salt spring,

casts its bodies in white steam. And the earth

opens for the spade …

There is an omniscient or prophetic quality to this tone, further emphasized by the choice that each sentence begins with “And…” The poem’s voice catalogues a world—and a language—that goes on and on and on.

My favorite aspect of the book is how it fosters mystery. Like all skilled poets, Schonning seems less interested in providing answers than in articulating meaningful lines of inquiry. In the poem “Dog Star,” I read the line, “Real things ask / so little of us” and wondered: what is meant by “real” things? Concrete things? Knowable things? In this poem, morning comes; the stars disappear. The “real things” line is repeated with a variation: “Real things ask nothing—not // even to be seen.” Perhaps real things are those that can be gestured toward or even witnessed, but fleetingly.

Throughout the book, there is a series of “[Little Box…]” poems with their titles in brackets, which I interpreted as a signal that these poems are a kind of interlude. In the Notes at the back of the book, Schonning explains that each “[Little Box…]” poem is a “syllabic pangram, a minimalist container in which each letter of the alphabet appears at least once.” For me, they function similarly to an ars poetica, and even more specifically, an ars poetica that speaks to the linguistic project of the book. In “[Little Box: Juniper],” a line reads: “In every poem is a quiet thing that it means to keep safe.” When I read “quiet” here, I thought of how the silence between sounds is an integral part of any language, of any poetry. Schonning takes care to show readers the dark sky between stars in a constellation, the silent space between each sound we utter. The emphasis on these conceptual gaps is one way space is created to invite the reader into each poem.

The opening line of the book is grand in scope: “At first, it’s as if all things are.” It seems to span all time and therefore prime the reader for a numinous encounter. The first five pages include no more than three lines of poetry per page. The white space of the page is yet another signal to the reader that they are being ushered into a meditative space. Eventually, the poem reaches the lines: “At first, there is nothing / but the terrible lightning.” The lightning here feels awesome in the original sense of the word. The white page becomes that flash of lightning before language arrives.

As the books winds down, the “Postlude” poem echoes the form of the “Proem” in a way that brings the book full circle, a reminder that time is not linear. “Proem” ends: “And the wet clay shakes alive. // And yes, the wild zinnias open their eyes.” At the end of the book, “Postlude” calls back to those images: “And the loose earth settles … And the wild zinnias, yes, close their eyes.” The journey through the world and through language is unending, but for now, we’ve reached a resting point. There’s an accumulation of meaning built through the repetition of these images—especially the use of clay, a substance imbued with mysticism, a place where body and spirit meet.

Several poems are written “after” other writers or include explicit references to famous thinkers within the poems themselves. There’s a richness this brings to the book; Schonning seems organically compelled to be in conversation with other writers. There’s a risk that some readers could find this alienating, that they may feel left out of the conversation if they don’t know the references. But I believe the intertextual quality of As When Waking makes it rewarding to read and reread because discovery remains possible upon each encounter. That makes it a book I want to keep on my shelf, a book to pick up again and again. Or, as Schonning might write: And again the poet picks up the book. And again light falls on the page. And—

Review by

Mary Ardery

11.06.25

Mary Ardery is the author of Level Watch (June Road Press, September 2025). Her poems appear in Beloit Poetry Journal, Best New Poets, Poet Lore, Prairie Schooner, and elsewhere. She earned a BA from DePauw University and an MFA from Southern Illinois University-Carbondale, where she won an Academy of American Poets Prize. She lives in Indiana. You can visit her online at maryardery.com

© Bear Review 2025

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Site Design + Build

October Associates