Bear

Reviews

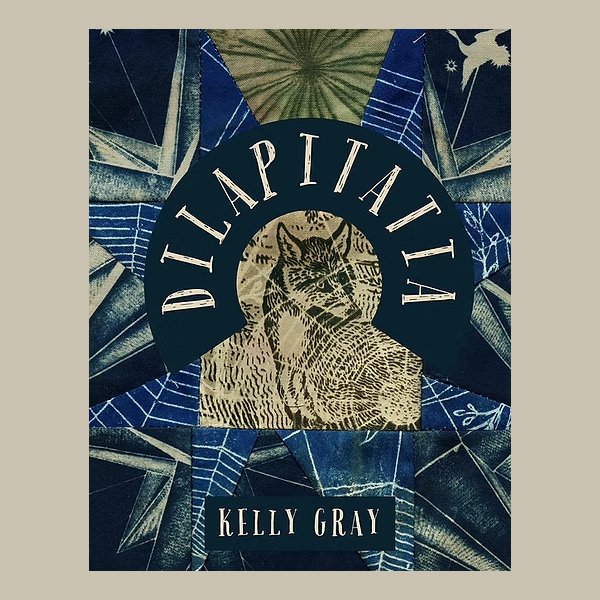

Dilapitatia

Kelly Gray

—

Obsessed with Obsession

Dilapitatia, according to poet Kelly Gray, is an obsessive disorder characterized by:

1. Recurrent and persistent thoughts about dilapidated structures and junctures

2. Finds it difficult or unable to control the need to be near dilapidated homes

An overture in poem form, this opening allows us to get a sense of the motifs that will populate the collection: songbirds, wild beasts, the concept of house and home.

We also get the message that this is a book about obsessions. Dilapitatia may be the nominal one, but the rest of the book will invite us to share in the cataloguing and defining of Gray’s obsessions with a degree of beauty and grotesque detail that makes this work worthy of our obsession with it.

The focus on home, not just physical, but what it means to have a place of origin and what that origin gives or takes from each of us, is a primary concern of Dilapitatia. Early in the book, in a poem called “In These Pipes, In This House, In This Field,” Gray lays the groundwork for the speaker’s origin by telling us:

I promised I would wait for my father’s death

before writing this, but the waters have been

rising for three weeks. I have forgotten how

to swimto him after he threw me in the pool.

My arms and legs learned what could not be

taught with kindness.

In the same poem, she invokes a grandmother and what may be heredity: “. . . she has a darkness / that will take too much paper to transcribe.”

There is more darkness to come. We learn about the speaker’s history in poems like “How the Fox Learns a Word,” where Gray writes:

That night, I set about the work of cutting into

my fox-self like a scientist, marveling at the

constellations found within my interior and

my ability to remain numb as I gulped the

stuffed clouds of couch cushions.

I tell you: that is control,

that is a blade.

That is not ostentatious at all.

The allusion to self-harm is paired with others that describe a history of mental illness and institutionalization (“When You Go To Bed with the Shape of Nabokov’s Mouth”), sexual abuse (“The Naming of the Stark Faced Child”), and disordered eating (“Eating Elegy”). Dilapitatia isn’t trauma for trauma’s sake, but an expression of the entirety of a life and the ability to craft a beautiful object out of a grim story.

The text also speaks to the disintegration of borders between what we may consider to be fixed or opposing concepts like beauty, ugliness, nature, humanity, death, life, and the self. In “Of Keyhole” we get a statement of philosophy that unifies the dark/light, inside/outside described in the book:

I do not believe

{anymore} in the idea of anthropomorphism.

Of attribution. Of

separation. Of

God, an object, Of the ghost, the animal

Of I am…

Take off your name. Remove your face.

We all lay down in the same bed.

Gray’s poems about parenting hit a primal chord that often remains subtext in conversations about the topic. In “The Problem I am Having is That Dying Can be so Loud with Death so Quiet,” the speaker begins by describing a relatively realistic journey to forage for wild mushrooms. By the end, she has shared her recurring dreams of losing her ill child, become the noncompliant wife of a buck, and spurned a hunter whose motivations aren’t yet known. She seduces the buck:

I would swallow his favorite doe

if I could, force him to take me as bride

Now I’m the four hooved whore of the underworld.

But when the buck demands that she “be-ith my possession, close your eyes against motherhood” she rebels, spontaneously creating magical, vulnerable children:

I grow a thousand teats, then, the fawns come.

Each one I love, each one has a neck shaped

like the inside of a cougar’s mouth. I stand

dripping milk as the buck bellows…

The speaker in Dilapitatia is deeply aware that, as written in “Wood Thrush as Ghost, as List,” “The corrosion of home is always multilayered.” She is determined to give her child the home she didn’t have, telling us in “The Watchers” that she is “writing a book about the sounds of foxes screaming/which is the sound of mothering while motherless.” The home the speaker provides will be whole, even if it means editing her own history. In the poem “Memory Abdomen”, she tells her daughter, “I have no backstory, so we throw all the words to the sky…” We have read enough by now to know that isn’t the truth, but it is one of the speaker’s many efforts to make a safe and beautiful home for her child.

This home that she is making is richly decorated and exists both inside and outside. There are banners hanging, deer speaking, and dresses for every occasion. There are cakes and pies being eaten. There are cameos from a dead mouse who may be some version of Emily Dickinson, Diane Seuss and Sylvia Plath as abortion providers, Molly Ringwald, and grifter Anthony Strangis. There is deep love in the home, between the mother and child, and eventually the hunter who approached in “The Problem I am Having is That Dying Can be so Loud with Death so Quiet.” The home they occupy is described in “The Brush of Arrow:”

My daughter eats pears, butter squash,

a blue egg found with blood stain,

and three pills

from a plate I built of clay.

He holds the plate like an invitation,

leaves his traps at the door.

I begin to bring him dead birds

to see if he can paint them fallen.

Dilapitatia is a lavish and ornate text, a world built to show how a world was built. It ends with A Clavis, where curious readers can find the author’s definitions of some of the lesser-known humans, words, and plants that populate the book. It is another act of careful building, of craft, that we have come to expect from the author by the time we have reached the end. And it is another enticement to read it obsessively: again, again, again.

Review by Allegra Wilson

09.19.25

Allegra Wilson is a writer living in Northern California. Her chapbook, song & ruins, received the 2025 Lefty Blondie Press First Chapbook Award, selected by Stacey Waite. She is the author of a micro-chapbook, sex party at the opera house(Whittle Micro-Press, December 2025), and her work has appeared in ANMLY, Up the Staircase Quarterly, The Inflectionist Review, and elsewhere.

© Bear Review 2025

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Site Design + Build

October Associates