Bear

Reviews

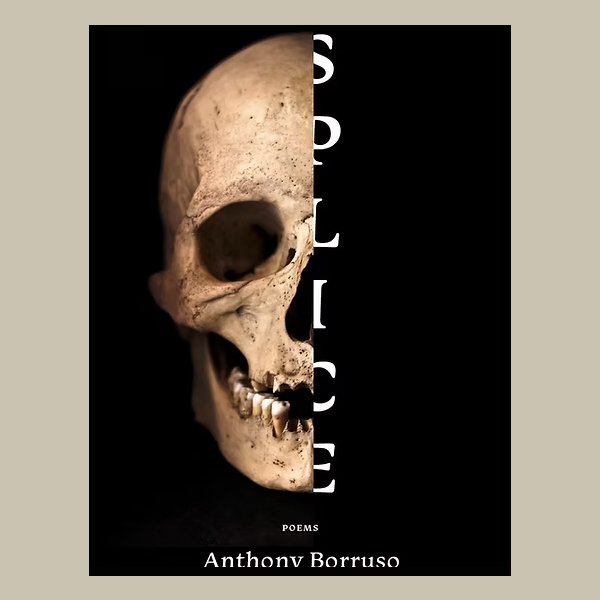

Splice

Anthony Borruso

—

Splice

Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Brain Surgery

The first poem in Anthony Borruso’s kaleidoscopic debut opens with “Do I have an original thought in my head?” which is itself not an original line, but a direct quote of Charlie Kaufman’s Adaptation, which opens with Nicolas Cage (playing a character named Charlie Kaufman) saying “Do I have an original thought in my head?” It’s a dizzying move that simultaneously announces the book’s themes and calls into question who, exactly, it is that speaks. The poem continues:

Malkovich is a vessel And I only have

to use the source material loosely My head is

a vessel This train throbbing to Montauk is a

vessel My love too and the sunny months we spent

quoting romcoms vessels What if in sleep someone

picks the lock of my eardrum What if I’m not the

protagonist

Just as in Being John Malkovich (the other Kaufman film referenced here), the speaker’s head is a “vessel” that someone could “pick the lock” of and enter, puppeting their speech and body. In this context, “What if I’m not the protagonist” rings with an urgent and existential dread. It also foreshadows the dynamic and shapeshifting voices that drive the book.

Splice constantly uses the lens of film to amplify deeply personal questions of identity and mortality. Film is an obsessive trigger, subject, and source for the poems in this collection, in which Emerson and Thoreau live easily alongside Hitchcock, Steve Buscemi, and Tilda Swinton. But while Splice is dense with cinematic reference, it does not require that the reader have an encyclopedic knowledge of film — indeed, a quiet personal narrative and the linguistic fireworks of Borruso’s persona poems are the true stars of the book.

A chronic illness narrative unfolds over the course of Splice, though the details are kept mostly blurry. The poem “Foramen Magnum” has an epigraph defining Chiari Malformation — a deformity of the skull which pushes a bit of the cerebellum down into the spinal canal. A more poetic description is provided in the body of the poem:

Did I mention my condition?

The brain, braving all elements, breaches its stony

fortress going god know where. What a headache,

to see this dumb snail trailing CSF down my back

and across every page of this manuscript.

This is as direct as the speaker gets regarding their illness. The actual condition, the poet’s surgery, and its attending emotional fallout are rarely centered as the subject of the poems in this book—refreshingly, Borruso is more interested in the aesthetic fracturing that results from “his condition” than any emotional distress. Even the most personal-feeling poems in the collection, while affecting, concern themselves more with the malleability of identity than with any confessional mode.

In “After Surgery, My Father Helps Me Bathe,” the speaker, “Jobless, 26,” sits in the shower in his father’s house where “steam obscures the boundaries between / me and my past self, 6, smiling, slamming // the head of a red power ranger on faded / ceramic tiles.” The father, a tougher figure, is giving the speaker a sponge bath after major cranial surgery. In this intimate moment, both men think of their pasts:

My father,

the policeman, who inhaled god-knows-what when

the city really didn’t sleep. When who he is now

stepped out from debris like a gray-tarnished twin

We are a kind of pentimento. Me and me

and him all living like stubborn

brushstrokes in a gilded frame.

Couched in this scene, specters of the past flicker into the present reality—“me and me // and him” all crowd into the oil painting frame of the poem. The doubled “me” evokes the speaker’s memory-fractured sense of self. Of course, even the “present day” speaker of the poem is now a fiction of the past, despite their aliveness on the page.

It would be irresponsible to go any further without mentioning how funny—truly funny—Splice is. Through all its questions of identity and death, it moves with a deft and joyful sense of play. In “Semi-Autobiography as SNL Cast Member” we watch the speaker in an early persona transformation:

I spin down the oil slick lane

a bowling ball in cahoots with the pins

did I mention i’m pete davidson or he is me

shaolin pilgrim at the deli buying gatorade

baconeggncheese I look diseased

The rhythms are wild, and the language struts with the sad swagger of rock-bottom Pete Davidson. The rhyme of “baconeggncheese” with “diseased” evokes brilliantly the mindset of a hungover bodega visit (I guffawed). Even in this loose-feeling poem, Borruso exercises remarkable control—by deploying a single lower-case “i,” we get the sense that the poet has momentarily wrested control of his body in order to clarify a detail to the reader. Then Pete takes back the wheel.

And there are countless examples of how powerfully the poet embodies these dynamic speakers. In “Hook’s Soliloquy,” nostalgia for youth is considered in a pirate’s lexicon (“Aye, Smee; I was once young too”). An ekphrastic to crooked faces (titled “Steve Buscemi”) opens “I don’t trust people with perfect teeth … I prefer // a face like a fender bender.” Ugliness then becomes a kind of salve against polite society:

give me the pricks,

the pissers, the ones who withhold

their tips from grey-eyed waitresses.

Give me the crooked paradise

of your mouth in a face that the world

seems to scaffold itself around.

All of these persona poems, in addition to being wonderfully “acted” and a blast to read, carry the poet’s bitter pill—the playfulness arises from the erasure of the self and the looming possibility of death.

In Splice, death is something to be feared and devoutly wished for (Hamlet, of course, also shows up in this collection). The conflicted death drive is addressed explicitly in “A Hypochondriac walks into Fourteen Lines:”

my body’s

that Banksy that shreds itself; it hums a

Morricone soundtrack facing off against the mind:

aneurysm, melanoma, heart attack,

on a toothpick I sample each savory demise.

Pairing a “Morricone soundtrack” with the series of delicious and deadly maladies evokes a bouncy optimism even as the speaker considers their own “savory demise.” This conflicted wish shows up again and again throughout Splice, always endowing the speaker’s fear of death with a lustful drive. It is hard not to feel the presence of Henry, John Berryman’s Dream Song stand-in, stalking these pages, and, to his credit, Borruso is not afraid to contend with Berryman’s shadow.

There is plenty of overlap: both speakers are obsessed with death and both speak with a hyper-textured modernist syntax. Borruso’s “I” certainly has flashes of Henry’s raging Id (from “At the Reception Desk:” “my father drives me to the hospital / in a minivan and brings me to a very kind receptionist / whom I tell to go fuck herself”). The poet acknowledges further similarities in “Under the Water or Whistling”:

And I’m sure we touch at certain points.

A dentist might marvel at the sharpness

of our canines. A psychoanalyst might unravel

the caution tape that mummifies

our mothers. But I am alive and I’m not going

to let Henry catfish me. My lyric “I”

is oil slick and merrily, merrily, confessing

supposed sins, a smiling Steamboat Willie,

with violent urges and whistling resourcefulness.

But clearly the poet also wants to wedge a little distance between them. Borruso’s lyric “I” is generally more affable, more self-aware and self-deprecating in his death drive than Henry—you’d never catch Henry singing “merrily, merrily.” And despite their shared slipperiness, there is a 21st century earnestness, a childlike play in Borruso’s shapeshifting. Ultimately, as the speaker states, “I am alive;” the title “Under the Water or Whistling” is a macabre nod to the respective fates of Berryman and Borruso.

In Splice, personal narrative is de-emphasized in favor of persona’s artifice, yet somehow the collection feels even more intimate because of this. This is due to Borruso’s profound trust in the intelligence of the reader and the fact that he never reaches for the sentimental to smooth the reader’s journey. Instead, his speaker takes us on a bumpy and blackly humorous existential journey — a death romp. It is a great credit to the talents of the poet that even in the book’s moments of highest artifice, it feels as though we are sitting beside a friend in a darkening theater as their most private thoughts materialize on the screen.

Review by Quinn Franzen

09.11.25

Quinn is an O'ahu-raised, Brooklyn-based actor, poet, and tutor. His poems are published or forthcoming in Poetry Magazine, Pleiades, Fugue, The Journal, Barrelhouse, and elsewhere. He was a Galway Kinnell Scholar at Community of Writers and received his MFA from the Bennington Writing Seminars. His acting work can be seen on TV, on- and off-Broadway, and in regional theaters across the country. Quinn lives in Brooklyn.

© Bear Review 2025

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Site Design + Build

October Associates