Bear

Reviews

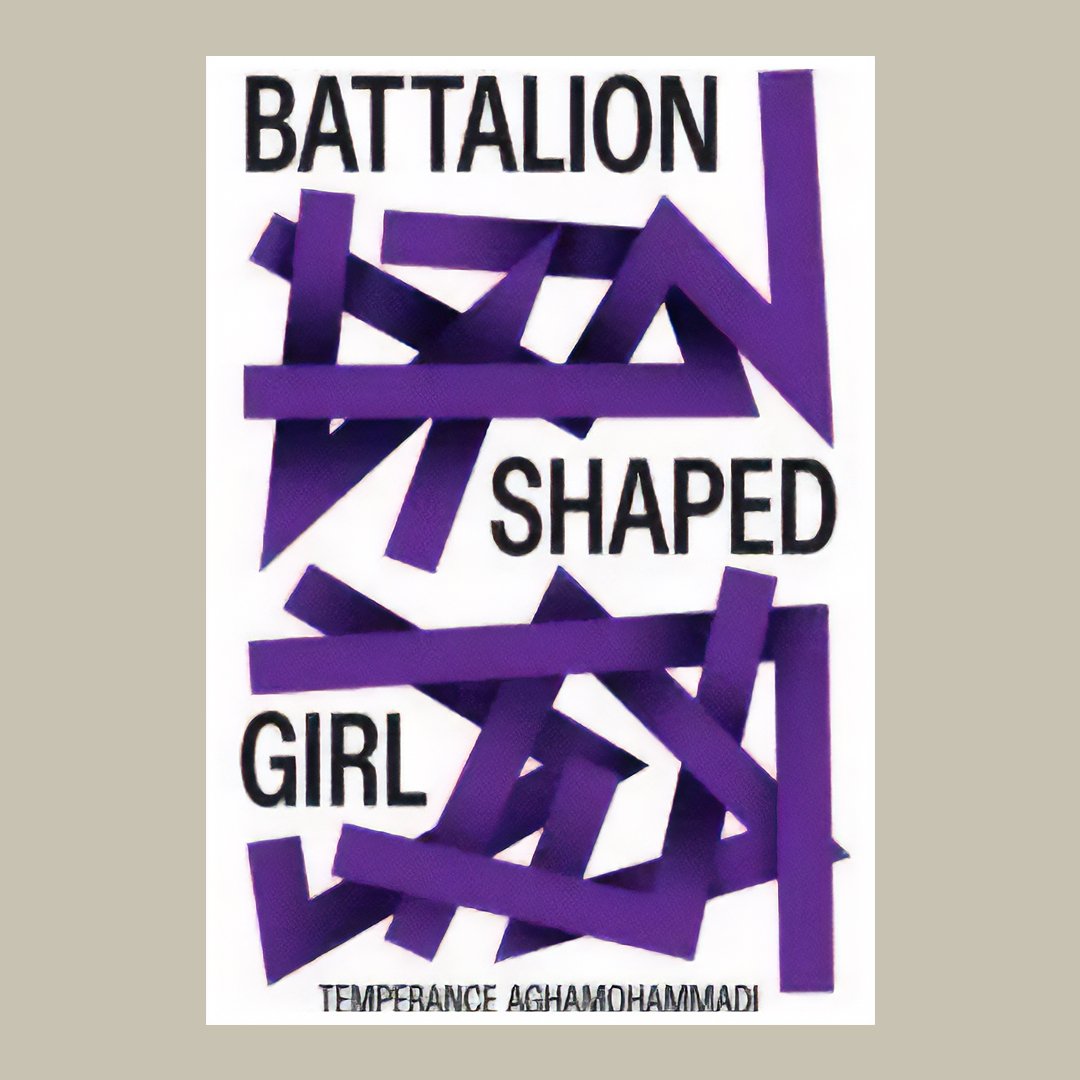

Battalion Shaped Girl

Temperance Aghamohammadi

—

Otherwordly Rhythms: The Sounds and Sensations of Temperance Aghamohammadi’s Battalion Shaped Girl.

A notable winter it was not, which is typical of Charleston, West Virginia. On my mind at this time primarily was dates: with friends, with family, with myself when I required an ample break. The latter occurred at Taylor Books, with its red store front, discounted paperbacks piled at attention, and the New Directions shelf with which I was so acquainted. It was during this winter I pulled a translation of Farrough Farrokhzad’s selected works aptly titled Let Us Believe in the Beginning of the Cold Season: “I wish I were like autumn / I wish I were…the leaves of my desire would turn yellow one by one.” Texas yellows now, and my wife is adamant about pointing it out amidst all our prevalent doubts; a bud pointed like a snout, remarkably and unmistakably gold. Brilliant. It was during this autumn I became acquainted with more brilliance: the work and presence of Temperance Aghamohammadi, an acolyte of the exquisite and now hauntress of the Midwest. Her debut collection, Battalion Shaped Girl, exhibits fork-tongued desires that glow and harrow, that take up Farrokhzad’s mantle and transform it, examine it, and ultimately, constructs a curio of sensual experience.

Aghamohammadi is not shy, nor do her poems shy away from heavy, necessary repetition. When wielded by another for mere show, this device can render a poem empty and redundant. In this collection, repetition is tempered with attentive variation; Aghamohammadi’s title poem asks us to witness subtle yet impactful shifts: “-shard. Field. Feathered / beast. Howling. / Angel calling. I wanted / to reach but” (2). Through simultaneous use of alliteration and progressive verbage, Aghamohammadi is able to transform glass shards to field, to feathered creature, to angel. Her associative leaps hopefully signal a shift in contemporary poetry, a return to the surreal where the complexities of imagination are once again present on the page, where the writer does not submit to an impulse that is solely narrative. This initial poem too makes an argument for the value of process; art is a continuum we must partake in: “Forever. / Falling” (2).

Battalion Shaped Girl is further unified by a numerical sequence of poems titled “Fetish,” which, based on my reading, draw one’s attention away from the sexual connotations of this term and direct one towards its predecessorial meaning. From the Portuguese, fetish is a term behnt (for you, Temperance) on charm, on creating an audience with what is mysterious. It was born of witness, to phenomena or ritual beyond understanding, that relies on sound to assist the body in its feeling of meaning (if such an end is possible). In this series of poems, Aghamohammadi is masterful in her selection of form, finding the constraints of the prose poem more generative than verse. While most contemporary prose poems read as lackluster micro-fiction, Aghamohammadi delivers not one but many mythological boxes (sorry, Pandora), relying on sonic play and punctuation to craft memorable scenes. The candle snuffed by fingers yields to corners, to “bloodlust bar[s]” where: “Incubi bare their crimson teeth. Death / whips her carriage down the street. / Your figure in shadow. A / nude. The Negroni tastes like light. Life like. Everyone arrives” (51).

Where to begin in my discussion of “Fetish IV,” where long e sounds and i glides summon such startling images; there too is that cheeky enjambment. To live in a world where “[e]veryone arrives” would be rather pleasant, wouldn’t it? Through devout end-stopped punctuation, Aghamohammadi sustains such marvelous tension between self and the social expectation of women: “Be skin soft. And postured.” Yet too, manages to turn such ridiculous notions on their heads: “To, the inferno with. Little ash. Love it.” The awareness that populates Aghamommadi’s poetry almost makes me believe she too shoulders the mantle of Fleabag: be elusive to your acquaintances, but oh so honest with your audience. Moments like “[Turn the cheek, Temp]” appear all throughout the collection, another notable instance in “There Are No Sound Machines” where she poses the damning question “Does the repetition of image render you witness or accomplice / [Voided]” in her exploration of violence and morality, a poem that refers to the murder of Mahsa Amini while she was in police custody (8). I am drawn to these assertions for their aurality; it is in these bracketed moments that the voice speaks so candidly.

It is not my first time encountering such artful deployment of this technique. In her translation of Sappho’s work, Carson utilizes brackets to create presence, citing that a reader should be implicated in her process: “why should anyone miss out on reading papyrus.” The brackets stand in for the human, for an experience that should not be missed. In “Fetish IV,” we leave the bar for the “Verily vanished,” a ride along the moon’s trail over rivers, onyx, and amber. We are reminded via brackets that the seatbelt light is “ON” and we better stay in our seats, thus risking the turbulence that comes with the serpentine. It is through these coy warnings we encounter such humanity, monotonous, day to day phrases, imbued with new meaning. This is poetry. The ability to adopt the real and recreate, animate. Aghamohammadi is “that girl. Torqued. Out. / Dismissed. Ms. This.” This concluding sentiment is Simone Weil in so many ways: through decreating ourselves, then do we as poets construct new worlds.

Aghamohammadi’s masterful deconstructions lead me back to the bow, to the idea that a girl is an ever-arranging fleet, and she must be. To tackle violence, insolence, shifting allegiances and economies. Through Aghamohammadi’s poetry, we witness mysticism in the militant, devotion in the hints, and what I can only sigh and name pure magic.

Review by

Kale Hensley

12.11.25

Kale Hensley is a poet, essayist, and scholar whose work bridges feminist poetics, mysticism, and literary history. Her writing has appeared in Booth, Image, Evergreen Review, Gulf Coast, and elsewhere, with multiple Pushcart and Best of the Net nominations.

Currently based in Texas, she is at work on her second collection of poetry that explores the avant-stupid and the glittering horrors of puberty.

© Bear Review 2025

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Site Design + Build

October Associates