Bear

Reviews

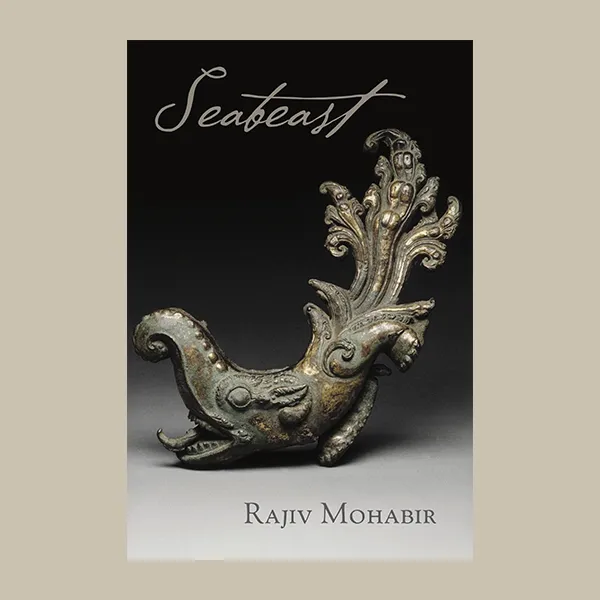

Seabeast

Rajiv Mohabir

—

A Taxonomy of Love and Loss

Guyanese poet, translator, and memoirist, Rajiv Mohabir, explores a taxonomy of love and loss in their fifth poetry collection, Seabeast (Four Way Books, 2025). In this litany of cetaceans and related species, both surviving and extinct, Mohabir documents the fallout of their queer marriage culminating in divorce, the loss of a relationship with their brother, and the effects of colonization. The matrix of species listed and their various histories serve as the scaffolding upon which Mohabir draws the strength to discuss these deep pains. If evolution yields vestigial organismal traits, now defunct parts of ourselves lacking function, in the aftermath we are faced with the question of how we must move forward. In Seabeast, Mohabir attempts to locate an answer.

In “California Sea Lion” we begin with mourning, of morning,

“red and gold like rays bleaching

your beard. I wanted”

all that is coveted and missed in a partner, now absent and haunting for their deception. If lineage is a tree that accumulates ever more branches, our relationships are everything that grows abundantly from the overflow. For that flow to now be stemmed is to witness a crown of verdancy collapse from those autumn branches. Mohabir weaves a devastating still life in “Bryde’s Whale,” more heart-rending for its poignancy:

“You were once beautiful

as my bride. The name for us

changing and changeable,

a wedding ring a bottom-

less basket.”

A marriage of two queer men in an ocean of gender fluidity, constantly evolving, now diverged. The image of the wedding ring as a basket woven without a foundation is striking. The word “bottom,” a term here also used to refer to the sexual role or power dynamic in a romantic partner, evokes the binary in the relationship with another romantic partner as the “top” and the shattering duality. Echoing Mohabir in “Fin Whale” where they,

“tried / to but couldn’t impregnate

my ex-husband because

Science muttered something

about biology, which once said

man is man, but now says

distinctions are more arbitrary”

In the analogy of the basket, the “top” or the giving partner fills the basket, pouring all of themself into its foundation. But when the bottom gives way, it is the giver who now finds themself with no foundation and an abrupt collapse. In this way, the ring symbolic of traditional, Western marriage falls short. Rather, than dismantling and deconstructing traditional marriage with this joining of queer individuals, instead their divorce underscores the flimsy bottom of the tradition of marriage as a societal construct that uplifts the same playbook rather than reimagining it.

These social constructs with roots in colonialism necessitate a new means of survival. The everyday struggle demands a re-invention of these systems into ones that are far more loving and unifying. Thus arrives the need, the requirement, to evolve. But this transition, like any healing, continues to unearth deep pains.

We see this in Mohabir’s poem entitled “INDOHYUS INDIRAE” which translates to “Indian pig,” an extinct Indian mammal significant to understanding the evolution of cetaceans from land to sea animals due to the Indohyus Indirae’s closest known relatives being whales. It is a transitional fossil and thus a pivotal species in the creation of new ones. In this poem, Mohabir pulls meaning from the density of its bone structure—

“. . . my bones

thick, help me submerge

to escape . . .”

—as well as the delicacy of the ectotympanic bone in the animal’s ear, drawing parallels with the evolution needed to survive one’s attackers while queer—

“. . . it’s simple to grasp

the need for aquatic life.

A predator from the street

or the sky casts its shadow

on my frame what choice

have I but to plunge.”

Here we find evolution as creation myth—an echo into ancestral inheritance Mohabir is familiar with from our shared Indo-Caribbean heritage. In a haunting line from their 2025 essay “To Regard: A Whale Watching Lesson” published in Washington Square Review Mohabir says, “The coolie was transported across the seas and were likely to hear the humpback’s plaintive echoes through the hulls of the repurposed ships.” Mohabir is thus the transitional fossil, the crucible of conflict-induced evolution, like our ancestors pivoting to attain homeostasis under duress from all this speciation.

Here also enters a brother, distant, both physically and mentally, as well as his abandonment. In the poem, “DORUDON SERRATUS,” we find a family: two closely related whales on the taxonomic tree, the basilosaurines and the dorudontines, the latter at times the other’s prey, an estranged relationship. Mohabir laments,

“and durable ice grows between

brothers like between me and mine

when his Orlando number

doesn’t shake my cell after

the latest mass murder where straight

men shot queers in Central

Florida.”

It is interesting to note that both basilosaurines and dorudontines lacked an organ that would allow the refinement of echolocation modern whales evolved to possess. The same might have been the case of two brothers. However, while one lagged behind, the other brother continued to transform—a mosaic evolution piecing together a more refined comprehension of a complicated ocean of connections in Seabeast.

Review by

Jay Aja

02.09.26

Jay Aja (dey / dem / he) is a poet and comics artist. They identify as transgender, queer, and second-generation-immigrant Guyanese. Jay’s work has been supported by CantoMundo, the Tin House Summer Writers Workshop, and the National Women’s Book Association. He’s published poetry in Foglifter, comics in The Rumpus, and received an Honorable Mention in the 2024 Tom Howard / Margaret Reid Poetry Contest. Jay has written poetry book reviews for Bear Review, Atticus Review, Saw Palm: Florida Literature and Art, and GRIFFEL. Find more of their poetry, comics, and book reviews on social media @ComicsBhaiJay

© Bear Review 2025

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Site Design + Build

October Associates