Bear

Reviews

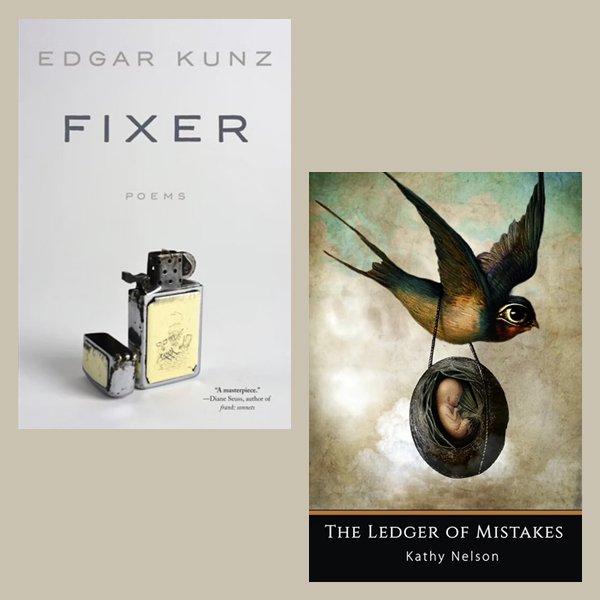

Fixer

Edgar Kunz

—

The Ledger of Mistakes

Kathy Nelson

Part of the project of being human is to be both a maker of mistakes and one who tries to fix them, to contain both creative and destructive impulses, and to grapple with what it means to hold these contradictory selves. How do we account for our own and others’ mistakes, and can they ever be repaired? These questions are at the heart of two recent books of poetry about imperfect parents and their adult children’s attempts to forgive the unforgivable. Kathy Nelson’s The Ledger of Mistakes and Edgar Kunz’s Fixer struggle with their speakers’ disappointment at the mistakes they’ve inherited, their far-reaching consequences, and how a person’s creations and destructions define their legacy.

The act of keeping a ledger of mistakes—one’s own as well as others—tells a lot about a speaker who would undertake such an activity: her unresolved guilt and anger, her inability to forgive herself and those she loves. For Nelson’s speaker, guilt for one’s own mistakes and anger at the mistakes of others are two sides of the same coin. In “Easter, 1956,” she reflects:

[...] I’ve lied and I’ve

been the one lied to, the advocate and the

adversary, the swatter and the fly, the witness

and the one

afraid to look. I have shrunk from the cliff’s edge,

and I have marveled at the possibilities of flight.

Here the speaker recognizes herself as marvelously complicated as well as unforgivably flawed. It is possible, she realizes, to be all of these people at once, to hold all of these truths in the same body. The speaker in fact takes pride in mistakes, those she’s made herself as well as those she’s survived. As she instructs in “How to Unknot a Straitjacket”: “Make a list/of the treasons you’ve earned.//Wreathe them around your neck like skulls.” A wreath suggests accomplishment; as the laurel wreath once signified athletic achievement, so the speaker has “earned” her disappointments and is even proud of them. But a wreath around one’s neck is also a heavy burden to bear. Moreover, the image of “skulls” calls to mind the realm of the dead, illustrating the speaker’s dual burden of grief for those she’s lost and anger at their transgressions.

Kunz’s speaker, too, keeps a running record of his father’s shortcomings, striving to improve upon them even as he is doomed to repeat history. After leaving a significant other, his speaker, like Nelson’s, expresses a desire to be punished, visibly marked in some way. In “Day Moon,” he says:

[...] I wanted

to be revealed by some visible sign

a welt to ride the ledge of my cheek

through the glass-littered

streets it didn’t come and it didn’t

come and I grew desperate

The poem’s incongruity between grammatical and linear units calls attention to how the lines themselves, like the speaker, are broken. “I was useless,” he says later in the same poem. After the death of his estranged father, the speaker is under pressure to fix the mess he left behind, but no one can ever “fix” another person. Ironically, the speaker reveals, his father used to be a “fixer” rather than a project who needed fixing, and is still remembered that way by those who knew him long enough:

Chris, she says, oh you mean Handy,

great guy, life of the party, the party

was always at his place, him

and your mom’s, plus he could fix

anything, he was amazing, leaky faucet,

done, sticky door, done, lawn mower

won’t start, done [...]

As its title suggests, Kunz’s book is about fixing, the unfixable, and the ability to recognize what can’t be fixed. Kunz focuses on both the manual labor of fixing physical objects and the emotional labor of coming to terms with an unsalvageable family and family history. The speaker’s string of temporary jobs and physical dislocations lead him to the realization that nothing can be fixed; he is getting nowhere. In “Model,” he describes a modeling gig that is ultimately a dead end: “When this is over, I will be paid//in gas station cards I’ll use to fill up/the car I borrowed to get here.” There’s an overwhelming feeling of pointlessness, of being caught in a circle. In “Shoulder Season,” he wonders, “How long can I go on/not finishing?”

How does one learn to reconcile, if such a thing is even possible, the damages done by someone who is long gone and cannot undo these damages themselves? This question is never answered, but rather explored through sharp, clear-eyed images. In Nelson’s “February,” “the rain-mirrored porch wears the bare trees,/and circles ripple out, one not quite gone//as the next drop bull’s-eyes the water.” Nelson’s speaker later situates this image in geographical relationship to her parents, who “lie on a hill overlooking I-40 two hours west.” The physical distance between the speaker and her parents then becomes psychic distance. She recalls her mother, “the bag she thrust at me—her sentences huffing/with scold, her lines end-stopped—inside, embroidery.//You’ll have to finish this. I’m unable.” The sampler, of course, represents what the mother is unable to say, or finish saying, to the speaker: “It reads My Daughter, My Shining Star.” After the mother’s death, the speaker is left to fill in the gaps in communication on her own.

Similarly, Kunz’s long eponymous poem, “Fixer,” the book’s centerpiece, deals with the physical aftermath of the father’s death: spaces, objects, odors, other things left behind in the material world that stand in for the absent figure of the father himself:

[...] Everything

we touch, you touched. Your socks.

Your coat. The cash in your pockets.

The cellophane from a fresh pack.

Zippo with a carving of a whale,

proud ship in the distance.

The speaker describes his reaction: “Tried to be respectful//like in a museum.” While ordinary things owned by a living person aren’t given much thought, when that person is gone, those same objects become sacred artifacts. In Nelson’s book, too, the deceased mother’s objects are given the weight of relics: in “Pot Liquor,” an otherwise ordinary salt shaker she describes as “that little Madonna//of generosity.” “I go on reaching for it,” she says, “The reluctance of water to boil or freeze as salt//is added.” In reaching for the salt shaker, she is of course reaching for the mother, emotionally reluctant even in life; now, in death, permanently unreachable.

Midway through The Ledger of Mistakes, we learn that the central mother-daughter relationship is further complicated by the memory of the father’s much earlier death, which set off a chain reaction of mistake, blame, and forgiveness. In “809 Whitehall Road, Knoxville, Tennessee,” Nelson’s speaker remembers:

Still, my mother demanding

once and never again:

Why did you leave him alone,

not even a blanket to cover him?

Me still running

across the empty lot for help.

The anaphora of “still” throughout the poem emphasizes that although the father’s death took place fifty years earlier, in a sense it is still going on. The cycle of blame and grief and guilt never stopped, only transformed into various iterations. Of course, neither the speaker nor her mother is to blame, but this doesn’t lessen the need to forgive themselves or each other for their own human imperfections, for still being in the world when he is not. In “Rivals,” the speaker attempts to explain her mother’s line of thinking, unfair as it is:

My mother never forgave me for being

the one who knelt beside my father,

my ear pressed, listening for his heart.

The list—the blanket, the ambulance—

all I could have done and did not—

hissed from her lips. If she could make

death my mistake, cast me out at last—

But she could not.

Here the speaker attempts to reach into the mother’s frustration with not having someone to blame. The lack of a scapegoat, the lack of facile answers or that cruel fallacy, “closure,” makes it more difficult to deal with the loss.

When to let go, to spare oneself and others, to realize the impossibility of fixing another person or the past? “We should have spared ourselves,” Kunz’s speaker reflects in “Fixer.” Here the speaker’s awareness that his father’s life, or rather the memory of his father’s life, is entirely dependent on him becomes too much to bear. Kunz continues:

when you’re the ground guy you got

to focus on the guy in the tree, you mess up

and that limb swings out and hits the line

bang the whole block goes dark

Being the “ground guy,” whether at work or in one’s family, is a role as impossible as it is necessary. If he is unable to handle that pressure for even a second, the speaker knows, the consequences can be catastrophic. In the speaker’s case, he has been the “ground guy” since childhood, while his father is the “guy in the tree,” signifying a shift in role and responsibility that neither the parent nor the child desires, and that both grow to resent. Similarly, in “Cake,” Nelson’s speaker recalls a rare moment of vulnerability on the part of her mother:

Just once my mother said, as if reciting,

as if she’d practiced, don’t know what I’d do

without you, then straightened, shrank away.

This brief lapse in the mother’s pride and resentment provides a window into her discomfort; forced to depend on her daughter for physical needs, she doubles down on the psychic distance she has placed between them.

In both Kunz’s and Nelson’s works, a parent’s betrayal—through some combination of death, illness, and estrangement—brings a maelstrom of decisions and complications. Both speakers are acutely aware of the need to leave the situation and spare their own well-being, but can never quite bring themselves to do so, even after the parent is gone. In “Tuning,” Kunz likens this phenomenon to a mechanical cycle of fixing and breaking, fixing and breaking, as with a car or watch:

Another loop

I’m caught in: suffering

and calibration. The punishing

miles, then the hours adjusting

the neatly clicking gears.

The striking enjambment, ending the line and stanza with “punishing,” calls back Nelson’s speaker as well, the obsession with guilt and punishment. Both speakers, like many people, instinctually find fault when something breaks that is not supposed to break. Objects are fragile; so are relationships. At the end of “Fixer,” Kunz’s speaker recognizes the pointlessness of trying to fix something he knows will fall apart the moment he steps away. He sees himself and his own situation in a piano tuner’s experience:

I met a woman once

who worked on pianos.

Said it was a hard job.

The tools, the leverage.

The required ear. I love it,

she said, but it’s brutal.

The second I step away

it’s already falling out of tune.

The metaphor is particularly apt in its connection between physical and emotional labor, fixing something with the hands and turning the heart’s many keys.

Ultimately, both Nelson’s and Kunz’s speakers find comfort in how love can be a way out of the endless cycle of breakage and repair: not a solution, but a sanctuary. In Nelson’s “Taco Tuesday,” the speaker takes delight in her growing family:

grandbaby on my shoulder, eighteen days,

already hoisting up her wobbly head,

daughter in the kitchen shredding chicken,

older grandkids showing me their homework

or downstairs playing foosball, husband still

here after all the ways I’ve maimed him [...]

Within the context of a self-described ledger of mistakes, born out of the speaker’s parents’ mistakes many decades ago, the promise of the present family—its still-hereness—is all the more astonishing. The labor of making something grow, while never repairing the past, can provide some measure of healing. Kunz’s speaker, too, describes how even the unlikeliest of people and places can be transformed by acts of love and rebirth. Towards the end of Fixer, the speaker revisits his deceased father’s apartment, “dragging/the mattress out and clearing/the maggots off the ceiling/with a shop vac.” Only by clearing the grime of the past, he learns, can the physical space—in addition to the emotional space the father left behind—be renewed. The presence of the speaker’s beloved further changes his outlook: “I wanted to show you where for/a while he lived and how and you/slung your arm around my waist.” After this gesture of love, the speaker begins to notice a more colorful array of details and images even in the forsaken apartment:

[...] bare

fluorescent bulb shining

on the Budweiser ashtray

the carpentry tools I would

inherit the ratty couch he crashed

on for years you held up

an old calypso record he loved

and sang out softly Jump in the line

“[H]ow astonishing how/astonishing what our love can make/of a place like that,” the speaker concludes. Love can’t change the past, but it can change our perspective on the past, the recorded history we create from it, and what we choose to carry forward.

Review by Liza Katz Duncan

06.24.25

Liza Katz Duncan is the author of Given (Autumn House Press, 2023), which received the Autumn House Press Rising Writer Award and the Laurel Prize for Best International First Collection, and Drought/Diagnosis (Southword Editions, 2025). Her poems have appeared in AGNI, The Common, The Kenyon Review, Poem-a-Day, Poetry, Poetry Daily, and elsewhere. A 2024-25 Climate Resiliency Fellow, she lives in New Jersey (Lenni-Lenape), USA, where she teaches multilingual learners.

© Bear Review 2025

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Site Design + Build

October Associates